http://zoharesque.blogspot.com/2025/04/valentina-gargarina-woman-who-stayed-on.html

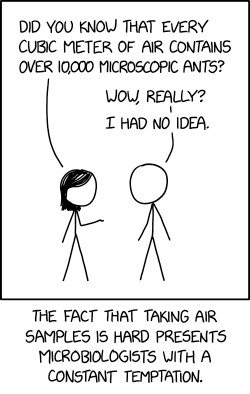

Every year on April 12 the world celebrates Yuri's Night, or the International Day of Human Spaceflight. The spotlight is on Yuri Gagarin who, on 12 April 1961, became the first human to come back from space. But this year I want to turn the spotlight on a lesser known person in the history of spaceflight: his wife, Valentina Ivanovna Goryacheva.

|

Valentina Gargarina, wearing glasses and a high bun, sombre expression

Image credit: Alexander Mokletsov / Sputnik |

In doing this I'm using a classic feminist method, to ask whose stories are not being told, and to centre a female perspective.

The young graduates

Valentina Ivanovna Goryacheva was born in the Russian city of Orenburg on December 15, 1935, the youngest of six children. Orenburg is located on the banks or the Ural river, close to the border with Kazakhstan. She was ten years old when WWII ended. Fortunately the city was far from the German invading forces.

She worked at the Orenburg Telegraph before starting a degree at the Orenburg State Medical University, but it's not clear whether she became a medical doctor or a medical technician. One account says she trained as a paramedic; in Burgess and Hall (2009), she says she was training as a nurse. Her daughter certainly referred to her as a doctor, and Andrew Jenks, in his 2012 biography of Yuri, says she studied medicine. Her work, however, seems to have been in biochemistry rather than medical practice.

She met Yuri Gagarin in May 1957 when he was finishing his cadetship at the Orenburg Higher Military Aviation School for Pilots. Valentina says they met during the May Day celebrations in Moscow's Red Square, where she was part of a nurse's gymnastics brigade. However, she also attended dances at the pilot's school. She was 22 and Yuri was 23. It was a swift courtship. They married in October 1957, the same month Sputnik 1 was launched. The marriage took place in Valentina's parent's residence at 35 Chicherina Street in Orenburg, and they lived there too, sharing a room with her parents.

In November 1957, Yuri was commissioned as a lieutenant in the Soviet Air Forces, and posted close to Murmansk for two years. Valentina joined him later and gave birth to Elena in April 1959, in the chilly conditions of the Arctic circle (Doran 1998: 27).

Stars on the horizon

Yuri was admitted to the Soviet Space Programme later in 1959 and they moved to Moscow. A new Cosmonaut Training Centre was opened in June 1960 near the Chkalovskaya airfield, and the cosmonauts and their families moved there along with all the civil and military personnel who worked at the facility. This facility later became known as Zvezdny Gorodok or Star City. Valentina took a job in the Mission Control Centre's Medical Directorate laboratory, which was in Moscow, and became pregnant again.

The original cosmonaut cohort was 20 men. Marina Popovich, herself a formidable pilot, was married to cosmonaut Pavel Popovich. She recalled: 'All of the wives thought that their husband would go first. You felt a hope, a fear, and a feeling of awe. It was an unbelievable sense of pride and wonder.'

In early April 1961, Yuri was selected to be the first human in space. Elena was two years old and Galina was just over a month old. When he left for the Baikonur launch site, he took with him a framed photo of Valentina (Burchett and Purdy 1961:23). On April 12, 1961, he orbited Earth in a Vostok spacecraft. It's difficult to feel now the uncertainty of this moment. Despite the launch of numerous animals, insects and plants into orbit, no-one really knew how the human body and mind would react. And the world was watching.

Valentina's watch

There are different stories about what happened next. I'm going to look at them through the lens of how they were reported in Australian press.

On Friday 14 April 1961 two days after the flight, The Canberra Times ran a story on page 1:Meanwhile Gagarin's shy, hazel-eyed wife Valentina and their two children await his return to their modest two-roomed flat, which he left several days ago without saying where he was going.

Special Task

The Government newspaper Izvestia quoted Valentina as saying she knew her husband had been training for a special task, but he did not tell her what it was. "He did not want to worry me because I was going to be a mother," she said.

Valentina's first news of her husband's achievement came when a woman neighbour rushed into the flat and told her to switch on the radio because they were broadcasting about him.

|

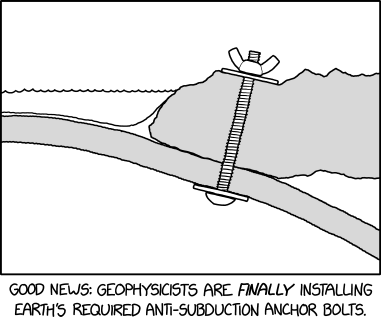

Canberra Times, Monday 17 April 1961 Picture of Elena's face wearing a bonnet; Valentina's face leaning against one hand.

|

If Valentina didn't know it was Yuri who had been selected, it does seem odd that photographers were on the scene to snap her and the family as they waited. These images were part of the press package released to the world. The photo of Valentina with her face in her hand has become famous.

It was important that Gagarin be presented as an ordinary person. He said in a press conference, reported by The Canberra Times on Monday 17 April 1961, 'I am an ordinary Soviet man, born on a collective farm. No princes of any kind are in my background'. Just as he had to be an ordinary man, so Valentina had to be an ordinary Soviet woman, shy and peasant-like.

This ordinariness was how the Australian Women's Weekly portrayed Valentina in a feature story on May 3, focusing on her.

'One of the proudest and most admired women in the world today is a dark-haired, unassuming young mother of two, with the romantic name of Valentina.

UNTIL two weeks ago, this young mother was just another Russian housewife. Now Valentina Gagarin's face has been televised and radioed around the globe'.

In this version of the story, Yuri has told Valentina beforehand; so she knew he was going into space. Krushchev apparently asked him if he had told her, and he was adamant that he had. Galina recalls that she knew what was going to happen, but not the exact day.

The feature story reports that Krushchev has credited her 'great soul' as part of Yuri's courage. She was the perfect wife in public: 'In every action there was happy pride, but not one of her gestures were awkward, affected or presumptuous. They were the movements of a woman who feels completely secure in herself and her husband'.

It also states that she trained to be a nurse at the Orenburg Medical School. It was not unusual for Soviet women to be doctors; but in Australia at the time, men were doctors and women were nurses.

Valentina performed a rite of womanhood here, just as the Apollo wives would a few years later: waiting for their man to come back alive from danger, prepared with a winding cloth if he should not.

The letter

When Yuri made his historic spaceflight, he wrote a letter to Valentina in case he never made it back. This is what it said (in English translation):

Hello, my sweet and much loved Valechka, Lenochka and Galochka

Here I’ve decided to write you a few lines to share the joy and happiness I felt today. Today a governmental commission decided to send me first to space. You know, dear Valyusha, I’m so happy; I want you to be happy with me. A simple man has been trusted such a big national task – to blaze the trail into space! Is there anything bigger to wish for? This is history, a new age!

The day after tomorrow is the launch. You’ll be doing you regular things then. It’s a very big task lying on my shoulders. I wish I had a chance to be with you for a little while before it, to talk to you. Alas, you are far away. But nevertheless I always feel you by my side.

I trust the hardware completely. It will not fail. But it happens that a man falls right on a level ground and breaks his neck. Some accident may happen here too. I personally don’t believe it would happen. But if it does, I ask you all and you, Valyusha, in the first place not to waste yourself with grief. Life is life, and nobody is safe from being run over by a car.

Take care of our girls; love them like I do. Please, raise them not as some lazy mommy’s girls, but real persons who can handle anything life throws at them. Make them worthy of the new society – communism. The state will help you do it.

As for your personal life, settle it the way your heart tells you, the way you feel right. I hold no obligation from you and I don’t think I have a right for it.

This letter seems too gloomy. I don’t feel like it. I hope you’ll never see this letter, and I’ll never have to be ashamed for this moment of weakness of mine. But if something goes wrong, you have to know it all. So far I lived an honest, rightful life; I served the people, even though this service was a little one.

In my childhood I read Valery Chkalov’s [legendary test pilot] words: ‘If being, then be first’. Well, I’m trying to be one and I will be to the end. I want, Valechka, to dedicate my flight to the people of the new society, communism, which we are about to become part of, to our great motherland, to our science.

I hope in a few days we will be together again and will be happy. Valechka, please, don’t forget my parents, and if you have an opportunity give them a helping hand. Send them my biggest greetings and ask their forgiveness for my keeping them unaware; they are not supposed to know anything.

This seems to be all. Goodbye, my dears. I embrace you all tight and kiss you. Your dad and Yura. 10 April, 1961.There's so much I could say about this letter but I'll leave it up to you to interpret.

Well, he wrote a letter for my mother saying that it was likely he wouldn't return, because the flight was very dangerous, and that he wanted her not to remain alone in that case. But he didn't give her the letter. She found it by chance among his things when he came back. He hadn't wanted her to find it, and told her that she should throw it away. But of course, she kept it.

After the spaceflight

As much as Yuri's life changed after he returned, so did Valentina's. She sat with Yuri and USSR leader Nikita Krushchev as they drove through the streets of Moscow in an open-topped car, cheered by adoring crowds. Initially, Yuri's mother came to help out with the children, and then they employed a nurse/nanny to stay in.

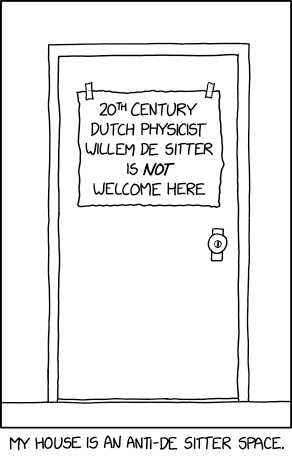

Valentina was awarded the Order of Lenin. She appeared with Yuri at official events and there were interviews and photos with the whole family. She travelled with Yuri on at least some of his post-spaceflight world tour over the next couple of years. This included India, Afghanistan and Japan. Here is a photo of her meeting the Japanese Prime Minister in 1962.

|

| Valentina Gargarina shakes hands with the Japanese Prime Minister, while Yuri looks on. |

Valentina and Yuri went to the opera (they saw Turandot in the Bolshoi Theatre for example), and they attended the wedding of Valentina Tereshkova on November 3, 1963. Many famous people visited the family. Despite being represented as a shy, retiring homebody, Valentina presided over a house always full of visitors. They entertained a lot.

It was not all plain sailing though. So-called 'womanising', drinking and violence to women were rife amongst the cosmonaut corps (Fraser and Tonkykh 2021). Program manager Nikolai Kamanin's diaries, full of gossip about the cosmonauts and their marriages, reveal a couple of incidents where Yuri was actively nasty to Valentina. He said that Yuri did not respect her and sometimes put her down (Fraser and Tonkykh 2021: 67).

Yuri got lots of female attention. Valentina caught Yuri in the bedroom of a nurse during a holiday in a Crimean resort with the other cosmonauts in September 1961, which must have been very painful. Yuri jumped from a second floor balcony to escape detection, and injured his face, leaving a permanent scar on his left eyebrow. Valentina was distraught (Jenks 2011: 118):

When Kamanin went out into the courtyard,

he saw Gagarin lying on a bench, his face covered in blood and a gaping

wound over his left eye. Gagarin’s wife was screaming, “He is dying!”

In some accounts, Yuri was forced to wear a fake eyebrow for a few weeks to cover up the injury (what). By now, the cosmonauts' behaviour had got out of hand. Yuri and Gherman Titov were severely disciplined at a November 14 Communist Party meeting, for 'acknowledged cases of excessive drinking, loose behavior towards women, and other offenses', according to space historian Asif Siddiqi (2000:295).

Divorce was on the cards for more than one cosmonaut couple. But whatever Valentina felt, providing evidence that the First Cosmonaut's life was not perfect would not have been an option.

Valentina did not see that much of Yuri since he had so many responsibilities. Galina noted in an interview in 2011 that 'he didn’t have much time to spend with the family. But we always spent every vacation together, and every Sunday, when he could, we would go to the countryside or visit someone.'

In photos taken for publicity in the 1960s, Valentina is often wearing glasses and has long hair braided into a chignon, or occasionally a beehive hairdo. She looks stylish in an understated way.

|

Yuri, Valentina, Elena and Galina at home in a striking red lounge suite. Elena is on the phone while Galina sits on Yuri's lap. Valentina is wearing a white dress with a beehive bun. The girls wear red and white and there is a vase a red and a white rose in it on the coffee table.

Image credit: Alexander Mokletsov /Sputnik

|

The year after Yuri's flight, the women cosmonauts came to Star City. Valentina became friends with Valentina Tereshkova, who became the first woman in space in 1963.

Yuri was the Deputy Training Director of the Centre from December 1963, and later the Director. As such he may have been Valentina's boss. At the least their work lives must have overlapped a great deal.

But it all came to an abrupt end. Yuri died in a plane crash on 27th March 1968. Valentina learned about the tragedy the next day. According to Elena,

Mom had a stomach ulcer, and she had just had an operation. Mom's sister stayed with us for the spring break. Then they brought Mom home from the hospital, and people started coming into the house. All in black. I think she had a poor idea of what was happening.

They had been married for 11 years. Sometime later, she opened the letter written to her in 1961, had he not survived: a message from beyond two graves.

Life after death

After Yuri's death, Valentina stayed in the apartment with their daughters, who attended school with the other children of Star City personnel. According to Wikipedia, a statue of Yuri clutching a daisy in his palm could be seen from her fourth floor apartment windows.

She didn't give any interviews. She was seen as shy and reclusive. She received a lifetime pension from the government but continued to work as a biochemist in the cosmonaut training centre.

She kept Yuri's large macaw.

What.

Gagarina is said to have a large macaw parrot, which her famous husband got. At that time, the bird was already 30 years old, and now it is over 80. But parrots of this breed can live for 150 years. The bird brightens up the loneliness of its owner.

The ara or scarlet macaw is native to large parts of South America, and Yuri had travelled there following his spaceflight. He went to Cuba on July 26 1961, then went on to Brazil on July 29. It's not clear if Valentina was with him. Caterina's (2020) account of the visit doesn't mention any gifts but it seems likely that the macaw was a result of this trip. What a journey to Moscow it must have had.

In 1969, the building Valentina's parents had lived in, in Orenburg, was turned into the Yuri Gagarin Museum. Valentina donated Yuri's personal things to the museum in 1976. They included his full dress jacket, awards, documents, presents, and the special editions of Soviet newspapers from April 12–13, commemorating his flight, which she had kept all this time. Maybe the boomerang presented to Yuri by Australian journalist Wilfrid Burchett's father was among the presents. But it wasn't all about Yuri. The room the Goryachev family lived in was made a 'memorial interior', as was the communal kitchen they used. The domestic, personal side of the couple was also there: 'The exhibits include authentic items from the first cosmonaut's family, such as a bedspread, curtains embroidered by Valentina Gagarina, and her dresses from the 1950s-1970s, which were donated to the museum'. Over time Star City grew from a small facility into a huge training centre. There were shops, cinemas, theatres, schools, sporting facilities. In 1973, five years after Yuri's death, the first American astronauts were welcomed. There were about 3,000 people living there in the 1970s. On Yuri's 50th anniversary, Michael Cassut, writing for the Smithsonian, noted: Over its lifetime, the center has trained more than 120 crews for launches on Vostok, Voskhod, and Soyuz spacecraft, or for trips to Mir and the International Space Station on the U.S. space shuttle. Most of the trainees have been citizens of the Soviet Union and Russia, but graduates of the center include more than 140 Americans, Europeans and Japanese, half a dozen Chinese astronauts, and all the world’s space tourists, from U.S. millionaires Dennis Tito and two-time flier Charles Simonyi to Canada’s Guy Laliberté and Iranian-born Anousheh Ansari.

Valentina was living through these changes to the space programme. It's not clear if she interacted with the influx of international space travellers, although all reports make mention of her famous shyness and reclusiveness. Valentina Tereshkova, however, always visited on her birthday and brought her a bunch of roses.

Letters to Valentina, Elena and Galina poured in from all over the world, long after Yuri's death. They were all kept in Valentina's flat. Some sent photos to go in the family archive.

She published a book of memoirs about her husband called '108 Minutes and a Lifetime' in 1981. In this book, she spoke of Yuri's positive qualities. But she did not gloss over things either, saying that he was often 'devilishly tired, upset and even angry' (Jenks 2011:121). She wrote a second book called 'Every year on April 12'. Sadly, these memoirs have not been translated and I have relied on second-hand reports about what they said. Ironically, her memoirs are usually used as evidence about his life, not hers.

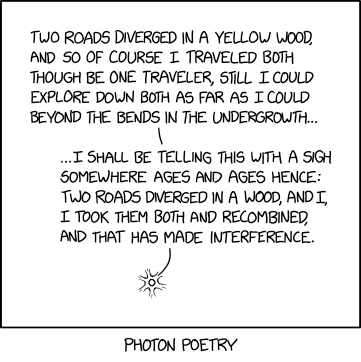

|

Cover of 108 Minutes and a Lifetime. Black with partial blue circle containing a headshot of Yuri in his space suit helmet. Image credit: Vintage Odessa Shop

https://www.etsy.com/au/shop/VintageOdessaShop?ref=nla_listing_details |

In 2011, she was awarded the Order of Gagarin, and in 2017, she was made an Honorary Citizen of the Moscow Region. On the 50th anniversary of Yuri's flight in 2011, Valentina was in her 70s and had retired.

This video shows Valentina at many points in her life, including Yuri's funeral and the 50th anniversary celebrations.

The madonna of Star City

They have a wonderful family tradition - to gather every year on Yuri Alekseevich's birthday for a modest feast in an apartment in Star City and indulge in memories of the great husband, father and grandfather. "When Katya [Yelena's daughter] was still a teenager, she once said at the family table that her grandmother was the happiest person in their family, because she had met such a man in her life that she had never needed anyone else. Valentina Ivanovna was surprised by these words at first, but then agreed: "In general, Katya, you are right," Gagarin's niece Tatyana Filatova wrote about those meetings in her memoirs.

Jenks has noted (2011:131) 'Those

close to Gagarin, including the Russian Federation government, cling

ferociously to the ideal image of Gagarin'. Some family members vigorously resist any attempt to paint him as less than a saint.

Valentina's surprise at Katya's comment suggests that she didn't think of herself, or Yuri, in this way at all.

She did not remarry. Much is made of this fact; it's mentioned in all the biographies. A purity was expected of her as if she had been sacralised by intimacy with the first man in space. As Allen Abell reported on the 50th anniversary, she tells her friends that she is tending to 'a fragile and perhaps still-broken heart'. Fragile, maybe, but was the 'still-broken' part of the expectation?

Viktor Gorbatko, one of the original 20 cosmonauts, told Allen Abell that 'She was more of the home type'. In most accounts she was a homebody who shied away from the spotlight, in keeping with the simple peasant girl ideology. But this is the woman who met heads of state, became a single mother at the age of 33, and worked as a doctor and scientist for three decades or more. Maybe there is more to be said.

Star City was not an easy place to live in the 1960s. This is how Michael Csssut describes it:

During the glory days of the 1960s, residents had special access to food and consumer goods, and lived in apartments that were double the standard Soviet size. The price for these privileges was submission to strict military and KGB control.

Maybe Valentina wasn't shy, this woman who navigated single motherhood and global fame. Maybe she was strategic, with the Communist Party no doubt monitoring her closely, and a new party leader - Brezhnev - who wasn't as glamoured by the cosmonauts as Krushchev had been. Maybe one marriage enchained to a man was enough.

The space medicine pioneer

The detail that she worked at the Mission Control Centre's medical laboratory is repeated in all the articles but no-one says what this means. Nor is there any mention if she continued to work there after moving to Star City or transferred to one of the other facilities. This aspect of her life is glossed over in both English and Russian sources (those I've been able to find). I imagine she may then have been employed at the cosmonaut training centre. So I am going to interpret this, read between the lines, and talk of it as her chosen career.

She was a space scientist, working on biomedical aspects of the Soviet space programme for her whole working life. She was working in the nascent field of space medicine, only about a decade old at that time. She may have been involved in the medical assessment, pre- and post-flight, of the male and female cosmonauts. The laboratory workplace and her degree suggests human sample testing and I'm sure I have seen a photo of her in a white lab coat with a microscope! I can't find it now, alas.

There was much a biochemist might have worked on in the space programme. There were research institutions all over Russia working on different aspects of this, as a top-secret CIA report enumerated in 1962; but at Star City they were in direct contact with the cosmonauts. Her experience with different crews over the decades would have been impressive. Siddiqi talks about the establishment of Soviet space biomedicine described in a series of declassified Soviet documents from the late 1950s and 1960s. In 1958, biomedicine specialists requested the expansion of research and a new institute for space medicine from Soviet leadership, leading to the Institute of Aviation and Space Medicine. Siddiqi says, 'This institute would later become the main force behind the selection and training of the first cosmonauts'. It's likely this one described in the CIA report:

Soviet Air Force Scientific Research Testing Institute of Aviation Medicine at Chkalovskaya Air Fields, 40 kilometers northeast of Moscow. Director unknown. This center, probably the second most important aeromedical research center, is equipped with two pressure chambers, two human centrifuges, and an ejection seat catapult probably of German World War 11 origin. Research has been done on pressure suits, preflight oxygen breathing, flight indoctrination and anti-G suits.

The first director in 1960 was flight surgeon Yevgeny Karpov, who presumably became Valentina's first boss.

Burgess and Hall (2009) talk about how the Cosmonaut Training Centre was set up:

Karpov’s appointment as head of the cosmonaut training centre was approved

on 24 February 1960. He quickly set to the task of working out how many specialists

and workers would be needed to staff the facility. As Kamanin recalled in his diaries,

Karpov submitted a proposal requesting a planned personnel of 250 people, but his

application met with understandable scepticism. “The deputy chief of the Air Force,

F.A. Agaltsov, smiled, appreciating the boldness of the 38-year-old colonel, and

reduced the staff to 70 people. Marshal Konstantin A. Vershinin listened first to

the colonel, then to the Colonel-General, and said to Agaltsov: ‘You, Filip

Aleksandrovich, don’t know how they will train, and neither does he.’ The Marshal

pointed to Karpov: ‘Look out. You must value this.’ And he confirmed the 250

personnel.”

The centre would be organized into a number of departments headed by Vladimir

A. Kovalov, Nikolai F. Nikiryasov (in charge of political activities), Yevstafi Y.

Tselikin (in charge of flight training), A.I. Susoyev and Grigori G. Maslennikov.

Medical specialists included Grigori Khlebnikov, H.K. Yeshanov (optic physiol¬

ogist), A.A. Lebedev (specialist of heat-exchange and hygiene), l.M. Arzhanov

(otolaryngologist), M.N. Mokrov (surgeon), V.A. Barutenko (oculist-surgeon),

A.S. Antoshchenko (hygiene systems, spacesuits, survival clothing), A.V. Nikitin

(therapist, attached to the cosmonauts for constant medical monitoring),

A.V. Beregovkin and others. The two senior trainers were Colonel Mark L. Gallai

and Colonel Leonid I. Goreglyad, both Heroes of the Soviet Union.

It's likely that Valentina was one of these 250 personnel but which section she worked in I can't discover with the sources available to me.

Did the other wives have careers too? It was usual for Soviet women to have an education and to work. Childcare was provided by the State. Marina Popovich, a pilot, was admitted to the cosmonaut programme only to be told that they weren't going to send a married woman to space (after two months of training). Her husband Pavel flew in 1962. He resented his wife's career and success deeply. Viktor Gorbatko's wife Valentina Pavlovna Ordynskayar was a gynaecologist. Vladimir Komarov's wife Valentina Yakovlevna Kiselyova was a graduate of the Grozny Teachers' Training Institute. Valery Bykovsky met his wife Valentina Mikhailovna Sukhova at Star City; later she became a historian in the museum there. Valentin Bondarenko was married to a medical worker, Galina Semenova Rykova. Many of the cosmonauts were single, but many were also newly married, and their wives were pre-occupied with new children.

So, many of the wives of those first cosmonauts had qualifications, but maybe not all had skills that could be utilised directly in the space programme. This gives some context to the work environment Valentina entered.

Of course, after that first intake of female cosmonauts, Russia basically excluded women from spaceflight with some limited exceptions. I once chaired a cosmonaut panel event in which a retired cosmonaut trainer said 'Space is no place for a woman' (the Australian audience did not react well and I had to shut discussion down fast). Even if Valentina did have ambitions in that direction, they could not be realised.

Valentina stayed on Earth but she was a space pioneer nevertheless.

Coda

Elena became director of the Kremlin State Museum. Galina is a professor of economics at Plekhanov University in Moscow.

Valentina Ivanovna Gagarina died on March 17 2020, at the age of 85, having failed to recover from a stroke.

Note

I've done my best with limited English-language resources, but no doubt there are many inaccuracies. I used the Google 'translate' function to access some Russian news stories.

In using a feminist methodology to write this, I have, for example, changed passive words to active words, so that things didn't just 'happen' to Valentina; she made them happen or made a decision. I've questioned the 'party line' about what she was like and tried not to use the common phrases and words applied to her. I also want to note the power of simply giving women their names.

And apologies for the weird formatting! I tried and tried to fix it without success.

References

Doran, Jamie 1998 Starman: The Truth Behind the Legend of Yuri Gagarin (50th Anniversary Edition). New York: Walker and CompanyBurchett, Wilfrid and Anthony Purdy 1961 Cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin. First Man in Space. London: Panther

Burgess, Colin and Rex Hall 2009 The First Soviet Cosmonaut Team. Their Lives, Legacy, and Historical Impact. Springer

Caterina, Gianfranco 2020 Gagarin in Brazil: reassessing the terms of the Cold War domestic political debate in 1961. Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional 63 (1), e004, Instituto Brasileiro de Relações Internacionais DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7329202000104 Fraser, Erica and Kateryna Tonkykh 2021 Cosmonaut gossip. Socialist masculinity as private-public performance in the Kamanin diaries. aspasia 15(1): 61–80 doi:10.3167/asp.2021.150105

Jenks, Andrew 2011 The sincere deceiver. Yuri Gagarin and the search for a higher truth. In James T. Andrews and Asif A. Siddiqi (eds) Into the Cosmos. Space Exploration and Soviet Culture, pp 107-132. Pittsburgh, Pa: University of Pittsburgh Press

Jenks, Andrew 2012 The Cosmonaut Who Couldn’t Stop Smiling: The Life and Legend of Yuri Gagarin. DeKalb, IL : NIU Press

Siddiqi, Asif 2000 Challenge to Apollo: the Soviet Union and the Space Race, 1945-1974. Washington, D.C.: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, NASA History Div., Office of Policy and Plans

http://zoharesque.blogspot.com/2025/04/valentina-gargarina-woman-who-stayed-on.html